"...and there he was, ragged, splendid, wild, sticking out of the expectable heraldry of the national pastime like a gigantic puce-and-mauve sore thumb rampant on a field of snow-white jock straps..."

In 1976 professional baseball invented a Man of the Year Award specifically for Mark Fidrych. In December of that year he flew from Massachusetts to L.A. for the ceremony, which was staged as part of the Major League Baseball annual winter meetings.

Before the ceremony, Mark was a bit nervous about the prospect of rubbing shoulders with Hollywood celebrities.

We were hanging out after, and I asked him what the show had been like.

He boarded one of his inimitable milk-run "trains of thought."

"Man, I just had a whale of a time. I met Don Rickles, Frank Sinatra, Monte Hall, Cary Grant, Pat Henry...Y'know, when I first went there, I said this is gonna be--this is gonna stink. To me, y'know? Because I just felt that it wasn't what I thought it was--y'know, what I wanted it to be. But then, as it was, it turned out they really treated you well. Very well, y'know?

"But these guys--I'll clue ya, these actors, man, they were neat. I just never thought it'd be that much fun. I mean, are you kiddin' me? My mother woulda went nuts to meet Cary Grant. And Frank Sinatra! She'd have been goin' nuts! Because that's the age that she grew up in, y'know? And like to me, it was just neat meetin' em. But my mother, oh, that woulda--it woulda been her highlight, if ever. It was a highlight to me. Like Monte Hall was probably more of a highlight to me, because I've watched Monte Hall. You know what I mean? Where Frank Sinatra, his stuff I really didn't watch too much except for if he was in a bad-ass movie, y'know?..But Cary Grant, I used to see him a lot, y'know? But Monte Hall I'd have to say was really the guy that--cause they just cracked up laughin'. I said, Hey--this guy goes, Here, you wanna meet Monte Hall? I said, Whoa, no, don't tell me that!"

From No Big Deal: photo Clifton Boutelle

_________

Sports Illustrated

In Which Today's Most Popular Bird Whistles Some Pretty Funny Tunes

Percy Bysshe Shelley certainly was a great poet, but he obviously knew from nothing about baseball:

Hail to thee, blithe spirit!

Bird thou never wert....

As baseball fans in Detroit and elsewhere can tell you, the line has got to read, "Bird thou always art...." for Mark (The Bird) Fidrych of the Tigers is one of the blithest spirits baseball has ever seen, heir to the tradition of heroic innocence established by such men as Rube Marquard and Germany Schaefer and carried on by the likes of Casey Stengel and Dizzy Dean. The tradition seemed to have run out of gas in this age of big-bucks baseball, but Fidrych has singlehandedly refueled it—and become, at the age of 23, a quasi-mythic figure in the process.

Myths and legends all seem to have their ghostwriters today, so it's no surprise that Fidrych has produced something called No Big Deal (Lippincott, $8.95), in collaboration with a writer named Tom Clark. But this being Fidrych, this book is different. Instead of an as-told-to autobiography it is done in question-and-answer form; and instead of your basic for-kids-only hagiography, it is pretty much warts-and-all—though The Bird, predictably, sports some amusing warts.

Clark says in his introduction, "Interviewing Mark is like being thrown into the water at an early age. You learn how to float in time, then you take a few strokes, then you're in the swim of it." He's right. Fidrych talks in waves and floods, splattering his sentences with apostrophes and italics and exclamation points. When he gets excited he's likely to shout, "Voom!" (he loves cars), and when he doesn't like the flow of the chatter he'll cry out, "Whoa!"

He is also a very, very funny talker and he loves to tell stories. My favorites revolve around the days when he played in the Appalachian League and lived in the Jim Dandy Trailer Camp, but others may fancy his encounter with Elton John ("He goes, I know a little bit about you. I said, Whoa. He's shock-in' the hell outa me.... I was lovin' it, though"), or the time Mickey Stanley visited his apartment and checked out all the groupies hanging around. ( Stanley said, "...you oughta make it a meat shop. Put numbers out there, it's so bad.")

Fidrych stories are like peanuts; once started, you can't stop. Since No Big Deal is full of them, it may well prove to be the funniest sports book of the year. Voom!

________

"Because, 'hey, that's what you call life.'"

________

New York Times

April 13, 2009

Mark Fidrych, Baseball’s Beloved ‘Bird,’ Dies at 54

DETROIT — Mark Fidrych, the golden-haired, eccentric pitcher known as the Bird, who became a rookie phenomenon for the Detroit Tigers in 1976 and later saw his career cut short by injury, died Monday. He was 54.

His death occurred on his farm in Northborough, Mass., Joseph D. Early Jr., the district attorney for Worcester County, said in a statement.

A family friend discovered Fidrych’s body beneath a Mack dump truck, Early said. He appeared to have been working on the truck at the time. The Massachusetts State Police began an investigation into the accident, he said.

During the summer of the nation’s bicentennial, Fidrych (pronounced FID-rich), then 21, electrified the baseball world.

“He was the most charismatic player we had during my time with the Tigers,” said Ernie Harwell, the veteran announcer, who began broadcasting Tigers games in 1960. “I didn’t see anybody else who was as much of a character as he was."

Fidrych’s record in 1976 was 19-9, with an earned run average of 2.34, the best in major league baseball, and 97 strikeouts. His 24 complete games were the year’s best in the American League.

Fidrych was named the rookie of the year in the American League and finished second to Jim Palmer in the race for the Cy Young Award.

Called “the fidgety, 6-foot-3 bundle of nerves” by The New York Times, Fidrych had a mop of golden curls and a gawky gait that prompted a minor league manager, Jeff Hogan, to compare him to Big Bird, the “Sesame Street” character.

The nickname — shortened to the Bird — stuck, but his appearance was only one of Fidrych’s vivid traits.

He often talked to the baseball, fidgeted on the mound and got down on his knees to scratch at the dirt. Fidrych would swagger around the grass after every out and was finicky about baseballs, refusing to reuse one if an opposing player got a hit, and rejecting fresh ones he declared to have dents.

He liked to jump over the white infield lines on his way to the mound, with a wide, toothy grin that, coupled with his hair, made him easy to spot even from the upper reaches of Tiger Stadium.

“Everybody really had a fondness for this young guy, especially the young girls,” Harwell said. “After he got a haircut, they’d run into the barbershop to see if they could get the curls off the floor."

Mark Steven Fidrych was born Aug. 15, 1954, in Worcester, Mass. His wife, Ann, whom he married in 1986, and a daughter, Jessica, survive him.

The son of an assistant school principal, Fidrych attended public and private schools in Worcester and entered the 1974 amateur draft.

But Fidrych, a right-hander, was not picked until the 10th round, and he spent two seasons in the minor leagues before making the Tigers after spring training in 1976.

He threw a few innings as a relief pitcher and made his first start in May. He captured the attention of Tigers fans in his first game as a starter by throwing seven no-hit innings and allowing only two hits in a 2-1 victory against the Cleveland Indians.

A month later, Fidrych pitched the Tigers to a 5-1 victory over the Yankees in a nationally televised game in front of a capacity crowd at Tiger Stadium. Fans, who rocked the stadium with applause, refused to leave until Fidrych came out from the dugout to tip his cap.

Weeks later, he was named the starting pitcher in the 1976 All-Star Game. But he gave up two runs and took the loss as the National League won, 7-1.

Still, Fidrych’s reputation grew as the season progressed, drawing near-capacity crowds to stadiums across the country as he performed his antics and kept winning ballgames, falling one short of 20 victories.

The Tigers, who paid him the league minimum, $16,500, for the 1976 season, gave him a $25,000 bonus and signed him to a three-year contract worth $255,000.

Picking up a series of lucrative endorsements, including a deal with Aqua-Velva, an aftershave maker (he joked to The Detroit Free Press that “it was a lotion, not an aftershave, because I really wasn’t shaving yet”), Fidrych wrote an autobiography with the author Tom Clark called “No Big Deal.”

But as it turned out, his rookie season was his biggest.

Fidrych sustained two serious injuries as soon as the 1977 season began, tearing the cartilage in a knee while cavorting on the field in spring training, then suffering a rotator cuff injury during an early-season game.

“I was playing Baltimore in Baltimore, and about the fifth inning, something happened,” Fidrych wrote. “The arm just went dead."

The injury was not diagnosed until 1986, but by then Fidrych’s career was long finished. After 1976, he played in only 27 games through 1980. Released by the Tigers in 1981, Fidrych competed briefly with a minor league team owned by the Boston Red Sox.

His lifetime major league record was 29-19, with a lifetime E.R.A. of 3.10, in 58 games, all but two of them starts.

Fidrych went home to central Massachusetts, where he bought a dump truck, becoming a licensed commercial truck driver, and eventually his farm in Northborough, where his family owned a diner.

Fidrych returned to Tiger Stadium in 1999 for ceremonies marking the last game there. A cheer went up from the crowd when Fidrych pawed at the dirt on the mound.

“He was a little naïve, just a sweet kid, really,” Harwell said. “He captured the public’s imagination.”

________Cardboard Gods

April 13, 2009

Mark Fidrych, 1954-2009

By Josh Wilker

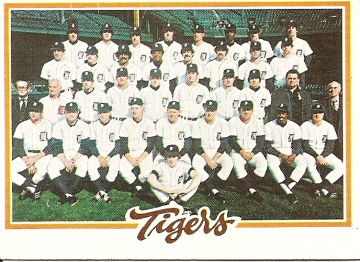

This 1978 card and another team card from 1977 are the last possible traces in my incomplete collection of the all-time single season leader in joy. I believe the Bird is in the back row, second from right. I’ve talked about him before on this site, but I don’t feel as if I’ve approached the singular effect he had on my childhood. To me, he was everything good from the 1970s wrapped up into one inimitable package. He’s the Pet Rock, mood rings, Morganna the Kissing Bandit, CB radio, Sasquatch. He’s Saturday morning cartoons and spaghettios and good-natured fun-loving longhaired yahoos piling into a customized van to go to the Foghat concert. He’s the magic of Doug Henning and the bright-colored fantasies of HR Puffnstuff and the glossy neon of Dynamite magazine. He’s Alfred E. Neuman. He’s that moment when you’re a kid and you start laughing about something and you don’t think you’ll ever be able to stop. He’s the moment when you realize you’re no longer a kid. I never knew him but to smile at him on TV and in magazines and, of course, baseball cards, but when I heard he was found dead today, underneath a pickup truck he was apparently trying to fix, I couldn’t breathe. For a couple seconds I couldn’t fucking breathe.

4 comments:

The world is a little less colorful for those of us who just enjoyed someone who was fully himself without being full of himself, who could make the Yankees look bad, no less.

Tom: I left a brief and dare I say entertaining salute this a.m., but it somehow didn't take. Let me then just say before dreams thanks for all your work and especially the curious case of el Fid. To paraphrase a wise man, no city ever needed a life preserver more. Except maybe the same city now. Glad YOU are on the mend and will spread the word on where to find you: here. yrs, yr faithful reader

Mark in 1985

Too much! My friend Bruce Shlain (whose own baseball book, Oddballs, features an illustrated Mark on the cover) reminds me this evening that he explains the Bird phenomenon to his now college freshman son thusly: "You see, absolutely NO ONE drew fans to the ballpark like that since Babe Ruth." You could look it up.

Post a Comment